About three and a half years ago I wrote about the sad fate of one of my dojo here in Osaka. It had been my “second home” for about 15 years, and 2020 would’ve been it’s 50th anniversary. As I wrote in the the linked article above, the disappearance of local dojo in Japan is not uncommon, and I am sure that the number of dojo that will get replaced by apartment buildings or car parking lots will continue to increase steadily over time.

My dojo had been visited by numerous famous sensei over the decades, and had served as the Osaka branch HQ for the All Japan Dojo Renmei, an association that looks after “shonen kendo” clubs (primary and junior high school age) throughout the country. Due to this, the dojo was decorated with various wall hangings featuring the sayings and handwriting of famous kendo instructors. There were also lots of other kendo related bits-and-bobs stored in cupboards and drawers here-and-there. Once we knew that the dojo’s future was compromised we had to decide what to do with everything.

In the end we there wasn’t any real plan: members just picked up something they liked, asked the sensei if they could have it, and stuck it in their bag. I wanted everything of course, but that wasn’t going to happen! In the end I took home a couple of famous sensei’s calligraphy (one in particular I had my eyes on for years), a massive (20-30 foot long) scroll that had been on the dojo wall (which I now have no place to put…), a handful of books, and a couple of curious scroll-canisters.

Calligraphy

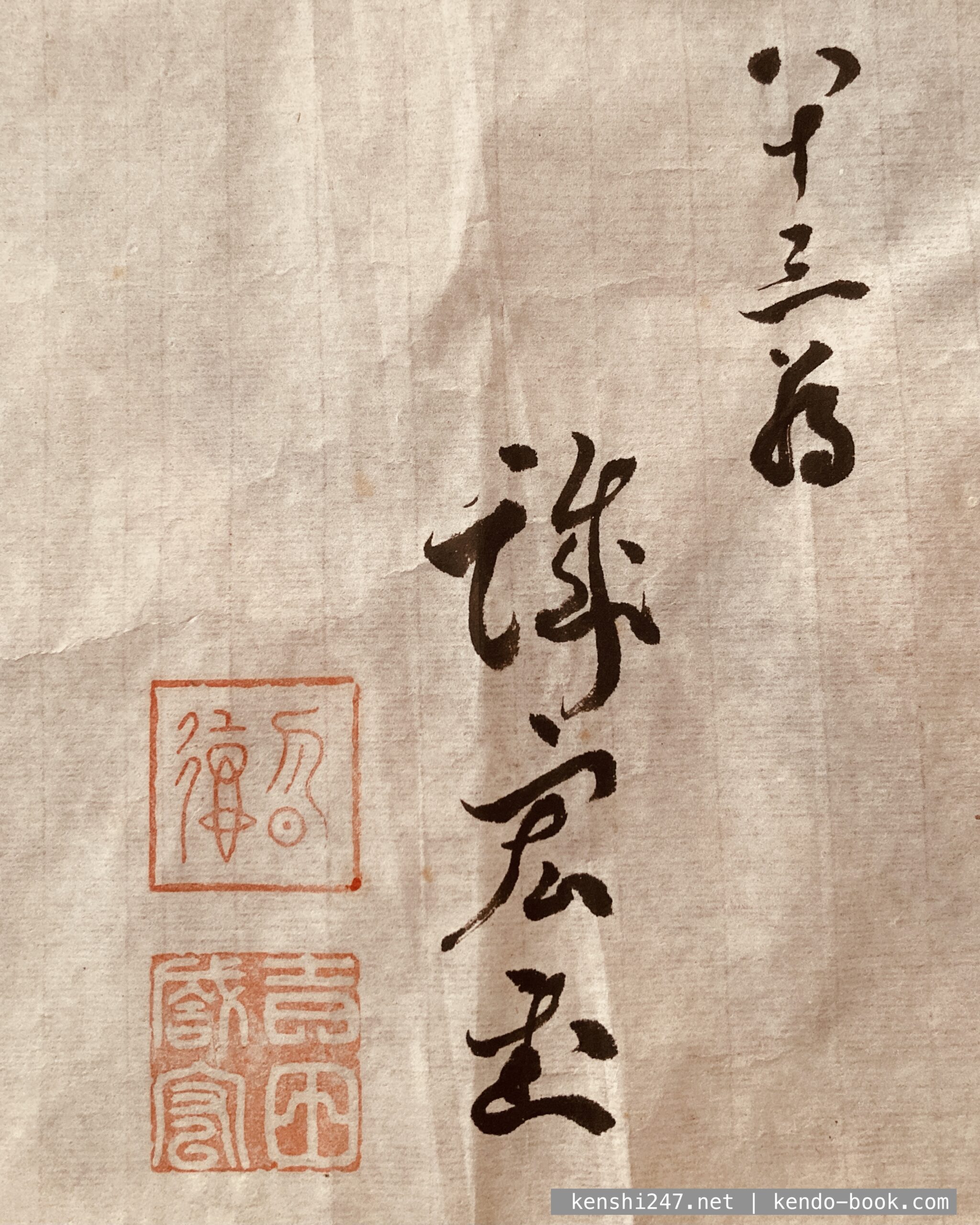

One of the scrolls I took home featured some beautiful calligraphy, reading from right to left: SHIN-BU-KEN (神武剣). SHIN-BU literally translates to something like (in our context) “heavenly martial arts/way” and KEN is of course “sword.” More accurately it refers to wielding the sword with virtue (The BU-TOKU of the Butokukai).

The calligraphy was by Yoshida Seiko sensei, a name I’d heard mentioned a few times by my sensei over the years, but whom I knew very little about other than he was well respected and extremely severe.

Yoshida Seiko

Born in Kagawa prefecture in 1889, Yoshida sensei graduated from the kendo-only (Koshusei) course at the Butokukai HQ in Kyoto, where he befriended the likes of Hori Shohei and Miyazaki Mosaburo (both later hanshi kyudan), before becoming a professional kendo instructor. I am unsure as to how long or even the exact dates he was in Kyoto, but he seems to have been there at least sometime around and/or between 1906-8ish (he went on a long Musha Shugyo with Hori in 1907, going to dojo the likes of Mito Tobukan and Yushinkan). The head teacher at the Butokukai at that time was Naito Takaharu, and other students around included Saimura Goro, Mochida Moriji, Shimatani Yashachi, Nakano Sosuke, Oshima Jikita, and Ogawa Kinnosuke.

What he did after graduating and before the war is also extremely sketchy – the only lead I found was that he worked as a kendo teacher at Ashihara police station in Osaka during the early 1920s.

What is known, however, is that he bought a building (which had been a restaurant called Eirakukan) in the valley between Nara and Osaka and reformed it into some sort of recuperation facility for tuberculosis sufferers in about 1937 (the whole area was some sort of recreation park between the 1910s and late 20s, which included an onsen, a pond, a small zoo, and a performance stage, as well as the aforementioned Eirakukan). Part of the property he renovated into a dojo called “Kusaezaka kenko dojo.”

Yoshida was no doctor, and it is said that his “treatment” was of his own conception based on his budo experience (e.g. breathing, rest, nutrition, stretching, exercise, reading sutras, lectures, etc). At the height of its popularity, it seems, there would be up to 100 people checked-in at one time. By 1942, however, with the war intensifying the place was failing, and it was closed permanently.

Yoshida lived only about a kilometre away from the dojo, at the base of Ikoma mountain, and there he opened (when exactly is unknown) another dojo called Seiwa dojo on the grounds of his property (he had enough land to be self-sufficient food-wise after the war).

Once kendo was restarted in the 50s he taught there to a wide variety of people, also hosting seminars and, it seems, continuing to run some sort of “mental and physical training dojo” (what this was exactly I am not sure – perhaps an extension of his earlier pseudo budo-clinic). He also became – at the very least – the kendo instructor at the Osaka Customs dojo as well as the local Dojo Renmei. My sensei’s sensei – the one who built the dojo that was dismantled – became Yoshida’s disciple in the summer of 1960 on the advice of Saimura Goro. He continued to study under Yoshida until his death in 1979.

BTW, one of Yoshida’s daughters is the noted Naginata practitioner, Sawada Hanae hanshi from Tendo-ryu. Following in her fathers footsteps, she was a member of the first class to enter the Butokukai’s Naginata Kyoin Yoseijo in 1934.

Samurai-like

Searching online you can find barely anything on Yoshida. The majority of the information you can find is from my dojo sempai, and he doesn’t know that much either! But what you can find – mostly anecdotes, it is clear that Yoshida was a very stern man who didn’t suffer fools gladly.

Most accounts call him a “Ko-bushi” which suggests that he had the air of an old warrior about him: physically and mentally strong, truthful, loyal, honourable, as well as morally principled. When people tell stories about him they always quote him in a brusque, directly to-the-point manner.

It is said that Yoshida didn’t bother with grades. However, I did manage to dig up evidence that by 1934 he had renshi (those that he had practised with in Kyoto were already hanshi or kyoshi by that time). He certainly didn’t grade with the newly established ZNKR after the war (when many people went from godan to nana or hachidan straight away), but we can probably assume he managed to reach kyoshi before the Butokukai was dissolved.

At any rate, he was in all probability a direct person who didn’t like to beat around the bush or deal with frivolities. His calligraphy – strong strokes, clear, easy to read – I believe, suggests this also.

JIN-MU?

Above I mentioned that the scroll read “SHIN-BU-KEN” but it is also possible to read it “JIN-MU-KEN.”

According to the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, the oldest books in the Japanese classical history canon, there was a battle between the mythical soon-to-be first Emperor of Japan, Jinmu Tenno, and Nagasune-biko, a local chieftain, in the vicinity of the dojo mentioned in today’s article. Yoshida’s dojo name – Kusaezaka – reflects the name of the area as found in the Nihon Shoki.

The kanji for JIN-MU (神武) is exactly the same as SHIN-BU above. Note also that the kanji for SEI-WA (聖和) dojo mentioned above could actually read SHOWA, the name of the current imperial era at the time today’s discussion takes place.

Considering the era that he was raised in, it is more than likely that Yoshida was highly nationalistic. In that respect, it is probable that the calligraphy I introduced here today has a double meaning.

Sources

昭和天覧試合 : 皇太子殿下御誕生奉祝。宮内省 監修。昭和9発行。大日本雄弁会講談社。

稽古なる人生。ブログ。